Feminism and the Legacy of Surrealism (Works)

Waxing Year 2, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 63 in. Courtesy of the artist and Bortolami Gallery.

Waxing Year 2, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 63 in. Courtesy of the artist and Bortolami Gallery.

Caitlin Keogh's work reflects on the construction of subjectivity and the constellation of objects that play a role in defining one's "self." Layering their multiple meanings, Keogh presents an expanded view of the place of the subject in history. In her own words:

"[The figure of the Waxing Year] comes from Robert Graves’s book, The White Goddess, about pagan poetry. I have been interested, since I started painting the figure, in the construction of subject positions in relation to making pictures, especially as they deal with gendered narratives in connection with creative production. Literary criticism is usually where I find the most elaborate and potent models. A subject position is not a rigid pose for me, but rather a para-explanation for the development of work, a way to sublimate the personal into 'someone else' and make more slippery the terms of self and depiction . . ."

"The flying penis in Waxing Year 2 comes from a small printed reproduction of what I think is probably a late 19th century erotic cartoon of an old crone selling flying penises out of a backpack (depicted in another work in this series) to young women in togas. (The source material is pretty inscrutable, stamped on the back by the department of contraband of the Neapolitan police). The floral motif comes from William Morris. The sprouting potato is my own. Other plants are taken from the book Étude de la Plante by Art Nouveau artist and decorator Maurice Pillard Verneuil. The postcard shows a roman antiquity. The mirror and ribbons are my own."">

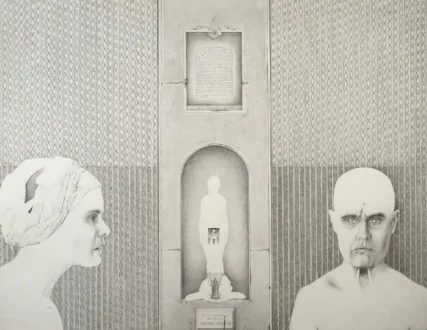

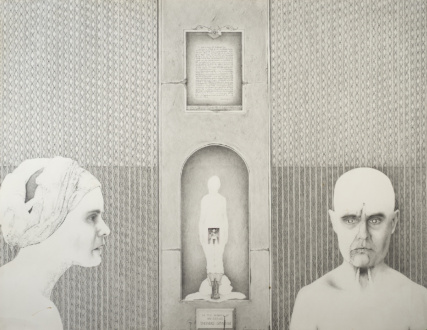

Aqua Bride, 1974/75. Graphite on paper, 30 x 40 in.

Aqua Bride, 1974/75. Graphite on paper, 30 x 40 in.

Writing about the altar-like arrangement at the center of Aqua Bride, Anne Minich delves into the source of her imagery in memory and personal history:

"A story about the image at her feet . . .

A story about the image of the vase of dead stalks . . .

My friend, Juan, when we were sharing studio space in Miami, was courting a new lover with the intention of having a partner in the NYC area.

He invited the man to Miami and we set to work sprucing up the studio.

Juan had been given a bouquet of red roses that eventually died as cut flowers will do. He left them in the vase thinking the man would see something sensitive, artistic, and meaningful; I told him the man might just see dead roses.

The man arrived and the first thing he said was, 'Why do you have a vase of dead roses?'

I'm not sure what the symbolism of the vase of dead stalks is, but it may have something to do with the above story.

When an image comes to me unbidden, I don't question it.

Thinking about the image as I write this, the image may be an unconscious way, at the time, of memorializing death as mankind has done from the beginning.

My work is a lot about death so the idea about the vase and it's contents isn't so far-fetched.

And there is the fact that the 'faggots' led to Joan's death.

The lace wrapped around my head was some of my grandmother's wedding stuff; I used it in a number of pieces; I don't know why beyond the fact of drawing it from life under an architect's lens, effectively shutting out the world that had become all but intolerable at the time.

It wasn't consciously about art but pure, raw obsession."">

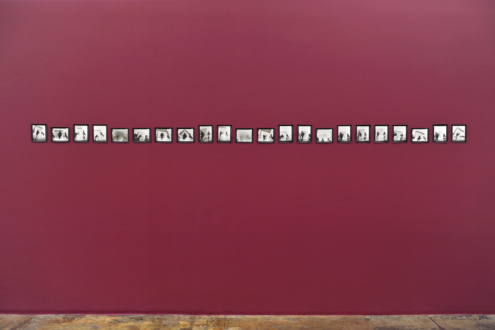

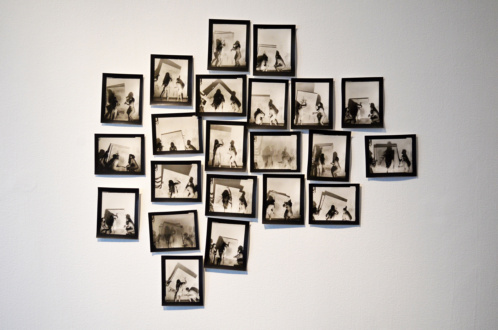

Studies for “Nudes Moving an Abstract Painting” 2013. 22 silver gelatin prints.

Studies for “Nudes Moving an Abstract Painting” 2013. 22 silver gelatin prints.

Elaine Stocki’s carefully staged and formally luscious images of nude women carrying abstract paintings revisit the aesthetics of 1970s-era performance documentation, combining that genre’s relationship to the provisional with a thoughtful, even classical approach to photography. The dark shadows cast by the protagonists and the illegibility of their action - its seeming lack of purpose - evokes a sense of ritual secrecy. Relaxing her previously stringent editing process, Stocki’s accumulation of images allows for a greater degree of insight into the performative genesis of these photographs and the enigma at their center.">

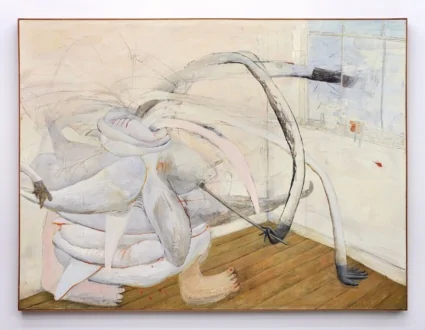

Madame Cézanne Falling Out of Chair, 1972. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 36 in.

Madame Cézanne Falling Out of Chair, 1972. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 36 in.

"Madame Cézanne Falling Out of Chair, is one in a series of four paintings using a composition style much like a cartoon-strip-format to analyze image, motion, and fragmentation.

Cézanne was immensely influential in Elizabeth Murray's early development as an artist. As a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Murray regularly passed by the works of Cézanne in the museum’s collection. 'The experience of looking at it took me from thinking about it as some kind of intellectual experience—which was what my teachers were all telling me. It was a real breakthrough for me when I saw that it was very sensual and clumsy in a certain way.'

For Murray, Madame Cézanne was a complex figure and as the subject of this series, Murray paints her in a simple diagrammatic domestic scene with the drama of a graphic novel. She uses a minimalist grid and stick-figures to establish narrative sequences much like a comic strip. This painting spells out frame by frame the subject dozing off and tumbling out of the chair, then getting up and reseating herself.

'These paintings were really important for me at the time. I did a series of four and I used the kind of cartoon format […] They’re to be read at the upper left hand corner across and down to the right […] But I think as clumsy and complex as the paintings are, I really started to work out with these paintings a kind of group of images and ways of thinking about space, the kind of topology and iconography for myself that I’m still pursuing.'"

— Jason Andrew, Director of the Estate of Elizabeth Murray">

Out of the Blue, 2018-19. Tin, wood, wire, and acrylic on fabric, 18 1/2 x 19 x 14 14 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hyphen Advisory.

">

Out of the Blue, 2018-19. Tin, wood, wire, and acrylic on fabric, 18 1/2 x 19 x 14 14 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hyphen Advisory.

">

Loretta, 2003.

16mm film, color, and sound, 3 min. 50 sec. Edition 1 of 5 (+2 AP)

Loretta, 2003.

16mm film, color, and sound, 3 min. 50 sec. Edition 1 of 5 (+2 AP)

“An abstract moving rayogram in the form of a woman or an aria. Living in time experienced as high drama, dissolving into the infinite. A dialectical manifestation of phenomena in flux, like any other movie.”

— Jeanne Liotta

Loretta was made by the artist through a painstakingly detailed process of creating photograms on the individual frames of the 16mm film. The photograms were made using original 35mm photographs as source material, combining strips of positive and negative film. The yellow hues were later applied by hand.

Writing about Loretta in Experimental Film and Photochemical Practices (2020), Kim Knowles argues that the film, “. . . is an example of how questions of materiality, the body, death and mourning come together in a forceful appeal to the senses. In many ways, Loretta stages the ‘death of cinema’ discourse by making visible and tangible the physical surfaces, edges, scratches, and grain of the celluloid, folding them into the ghostly image of a human figure that seems to undergo its own traumatic experience . … The film explodes onto the screen with a burst of yellow light, a corresponding explosion on the soundtrack immediately creating a complex fusion of the senses. A confusing array of abstract and figurative visual stimuli lashes out at the spectator with frenzied, hypnotic speed. From between the flickering images a disembodied human figures continually appears and disappears as if being washed onto the surface of the screen, only to be dragged back into a sea of film fragments, sprocket holes and material debris. The figure oscillates between black against yellow and yellow against black in a constant movement between figure and ground. A hand reaches out, as if appealing to the viewer, who helplessly watches the writhing, suffering body as it slowly dissolves into the abstract matter.

. . .

Representation and the difficulty of vision are central to how the film functions on an affective level: our eyes do not — cannot — fix or contain the image. Form and content, figure and ground are in a constant state of flux, a process of becoming that prevents one from dominating the other. Matter washes over matter in a ritualistic cinematic burial that sees death as an inevitable part of the earthly continuum.”">

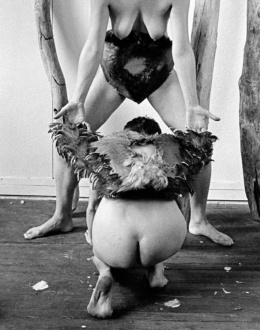

Body Masks (no. 3), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.

Body Masks (no. 3), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.

Betsy Damon’s Body Masks is a series of photographs from a 1976 performative session in the artist studio in New York City. Damon (b. 1940) started doing performance with the Feminist Art Studio, which she founded at Cornell University in 1972. Raised with an intimate relationship to nature, in Ithaca, set among hills, woods and waterfalls, Damon began exploring her female body as a powerful creative force. This connection with nature permeated both her feminist rituals organized with other women in the open, and wood sculptures that she created at the time. In 1976 Damon leaves Ithaca and joins the lesbian artist community in New York City. Materials such as feathers and palm tree bark enter the studio with her. Body Masks both conceal and reveal, shielding the artist while she creates and confronts her new self and new life – vulnerable, sexual, and preparing to step into public space. They presage Damon’s performance career which will begin a year later, which will be marked by a close collaboration with other women and her intimate relationship with nature – raw power of the female body and nature’s constant rebirth.

— Text by Monika Fabijanska">

Body Masks (no. 4), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.">

Body Masks (no. 4), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.">

Body Masks (no. 1), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.">

Body Masks (no. 1), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.">

Body Masks (no. 2), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.">

Body Masks (no. 2), 1976/2021. Black & white photograph, 24 x 36 in. Edition 1 of 6 (+2 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Monika Fabijanska Contemporary Art Projects.">

Green Scroll with Figures, 2008. Metal, wire, and acrylic on fabric, 21 1/2 x 27 1/2 x 10 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hyphen Advisory.">

Green Scroll with Figures, 2008. Metal, wire, and acrylic on fabric, 21 1/2 x 27 1/2 x 10 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hyphen Advisory.">

Untitled, 1973. Oil on canvas, 72 x 96 in. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Untitled, 1973. Oil on canvas, 72 x 96 in. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co."In 1972 my mother died. I was 29. My whole world turned upside down, and I was frustrated in my studio. Sometimes I would turn to sculpture during a transition to open things up. So I started making this large sculpture expressing the frustration of how to go about portraying the deep pain and loss I was feeling. The sculpture was of me painting this frustration. For the hands, I used my mothers gloves.

The sculpture was too large to even get out the studio door. So I started painting it and that got me excited to paint again. In 1973 I had my first one person show at the Willis Gallery in Detroit and you can see this painting on the wall behind the sculpture."

— Brenda Goodman on Untitled (1973)">

Not Long Now, 2021. Oil and mixed media on matboard, 12 x 16 in. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.">

Not Long Now, 2021. Oil and mixed media on matboard, 12 x 16 in. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.">

The Machine That Makes Itself. Wire, wood, and string, 14 1/2 x 23 1/2 x 13 1/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hyphen Advisory.

The Machine That Makes Itself. Wire, wood, and string, 14 1/2 x 23 1/2 x 13 1/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hyphen Advisory.

"In her eight decades of making art, June Leaf (b. 1929) has consistently explored and pushed the boundaries of the interrelations and intersections of painting, sculpture, and drawing. Figures and landscapes are primarily what she renders but the technical and mechanical resolutions in her work are often equally the subject. movement and sound."

Leaf comes from a generation that predates the women’s movement of the latter half of the 20th century but she has always stated that the “astonishing capacity of women” is something that she has sought to reveal and portray all along. This is in evidence in her 1970s series, the Women Monuments, and in the current exhibition in the sculpture The Machine that Makes Itself (2019), a miniature sewing machine handmade in wire with string; it has working parts but it is conspicuously absent of its user. Alongside will be two more kinetic sculptures by Leaf that incorporate painting on fabric and handmade cranks with gears. Each assemblage is a scroll, recalling early cinema through its movement and sound."

— Text by Andrea Glimcher, Hyphen">

Selected Works

Betsy Damon, Brenda Goodman, June Leaf, Jeanne Liotta, Caitlin Keogh, Anne Minich, Elizabeth Murray, and Elaine Stocki

Feminism and the Legacy of Surrealism Press Release

The artists in this show have been brought together by their affinity for the artistic and conceptual strategies of surrealism, using them to articulate a feminist perspective grounded in personal experience. While not surrealists themselves, they are a part of its legacy, taking up surrealism – which produced more important women artists than any other modernist movement – in its ability to tap into the unconscious. The paintings, drawings, films, sculptures, and performance photographs on view – by Betsy Damon, Brenda Goodman, June Leaf, Jeanne Liotta, Caitlin Keogh, Anne Minich, Elizabeth Murray, and Elaine Stocki – play with a private symbolism that merges elements of subjectivity with dream imagery and references to mass media. Seen together, the works in this show display a biting wit in the visceral quality of both their images and materiality.

The objects in Caitlin Keogh’s Waxing Year 2 (2020), painted individually with perfect precision, exhibit something uncanny in their total arrangement. They feel like discarded ephemera, often alluding to cultural signs of femininity, which have been excised from various sources and collaged together by the artist. Elaine Stocki’s grouping of small, black-and-white photographs (2013) show three female nudes moving a large, nondescript canvas. The dark shadows cast by the protagonists and the illegibility of their action – its seeming lack of purpose – evokes a sense of ritual secrecy. Both Keogh and Stocki create enigmas: works that estrange reality and reveal the subterranean links between the imagination and visual objects.

In her large-scale self-portrait from 1973, Brenda Goodman depicts herself at work in the studio. Like an ouroboros, multiple arms jut out from the artist’s mouth, some painting her likeness while others forcibly gorge her. This feeling of psychological stress remains palpable in her more recent work, visible in the incisions used to generate the now-abstract vocabulary of her paintings.

For Murray and Leaf, the repetitive nature of film plays a similar role, allowing them to fixate on a single moment and, by means of repetition, to extract its hidden suggestions. The kinetic sculptures of June Leaf, for example, incorporate painting with handmade mechanisms set into motion by a series of cranks and gears that recall early cinema in their movement and sound. In Elizabeth Murray’s painting from 1972, Cézanne’s portrait of his wife becomes the occasion for a slapstick routine, with a stiff Madame Cézanne falling out of her chair, revealing the absurdity of the scene by using a sequence of comic strip cells.

The other artists in this show – Damon, Liotta, and Minich – are united by the visionary, archetypal character of their work. In the photographs that document Betsy Damon’s Body Masks (1976) – a performative session in the artist’s studio – two women are adorned with an armor of feathers and palm husks that suggest exaggerated female genitalia. They stand, like fertility idols, headless, their torsos filling the frame. Jeanne Liotta’s film Loretta (2003) has a similar visceral quality, turning the projector’s bulb into the source of a kind of nuclear holocaust, silhouttes of figures, arms raised, flashing across the screen before being consumed by light. Finally, the work of Anne Minich is bound up with the creation of a personal mythos that attaches a spiritual, otherworldly significance to a certain period of the artist’s life. Borrowing its composition from church architecture, Aqua Bride (mid-1970s) is a double self-portrait that delves into the eros and corpus of Catholic theology, identifying Minich herself with the passion of Joan of Arc.

Made through an intuitive process that translates the mental state of the artist into visual forms, the artworks on view are charged with a libidinal energy. If, as psychoanalysis claims, the experience of modern life is one in which unconscious desires are ubiquitously denied – especially those of women – then these artists show how repression can be wielded for the sake of its opposite: to create works with a psychic force of their own.

![Caitlin Keogh, <i>Waxing Year 2</i>, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 63 in. Courtesy of the artist and Bortolami Gallery.

<br>

<br>

Caitlin Keogh's work reflects on the construction of subjectivity and the constellation of objects that play a role in defining one's "self." Layering their multiple meanings, Keogh presents an expanded view of the place of the subject in history. In her own words:

<br>

<br>

"[The figure of the Waxing Year] comes from Robert Graves’s book, <i>The White Goddess</i>, about pagan poetry. I have been interested, since I started painting the figure, in the construction of subject positions in relation to making pictures, especially as they deal with gendered narratives in connection with creative production. Literary criticism is usually where I find the most elaborate and potent models. A subject position is not a rigid pose for me, but rather a para-explanation for the development of work, a way to sublimate the personal into 'someone else' and make more slippery the terms of self and depiction . . ."

<br>

<br>

"The flying penis in <i>Waxing Year 2</i> comes from a small printed reproduction of what I think is probably a late 19th century erotic cartoon of an old crone selling flying penises out of a backpack (depicted in another work in this series) to young women in togas. (The source material is pretty inscrutable, stamped on the back by the department of contraband of the Neapolitan police). The floral motif comes from William Morris. The sprouting potato is my own. Other plants are taken from the book <i>Étude de la Plante</i> by Art Nouveau artist and decorator Maurice Pillard Verneuil. The postcard shows a roman antiquity. The mirror and ribbons are my own."](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/CK9711-02-1050x1400-1-248x330.jpg)

![Elizabeth Murray, <i>Madame Cézanne Falling Out of Chair</i>, 1972. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 36 in.

<br>

<br>

"<i>Madame Cézanne Falling Out of Chair</i>, is one in a series of four paintings using a composition style much like a cartoon-strip-format to analyze image, motion, and fragmentation.

<br><br>

Cézanne was immensely influential in Elizabeth Murray's early development as an artist. As a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Murray regularly passed by the works of Cézanne in the museum’s collection. 'The experience of looking at it took me from thinking about it as some kind of intellectual experience—which was what my teachers were all telling me. It was a real breakthrough for me when I saw that it was very sensual and clumsy in a certain way.'

<br><br>

For Murray, Madame Cézanne was a complex figure and as the subject of this series, Murray paints her in a simple diagrammatic domestic scene with the drama of a graphic novel. She uses a minimalist grid and stick-figures to establish narrative sequences much like a comic strip. This painting spells out frame by frame the subject dozing off and tumbling out of the chair, then getting up and reseating herself.

<br><br>

'These paintings were really important for me at the time. I did a series of four and I used the kind of cartoon format […] They’re to be read at the upper left hand corner across and down to the right […] But I think as clumsy and complex as the paintings are, I really started to work out with these paintings a kind of group of images and ways of thinking about space, the kind of topology and iconography for myself that I’m still pursuing.'"

<br><br>

— Jason Andrew, Director of the Estate of Elizabeth Murray](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/EMU_painting-334x330.jpg)