Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman (Works)

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Studio portrait of Louise Fishman, photographed 2019 by Nina Subin.](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/LouiseFishman1-e1636387137641-507x330.jpeg)

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Installation view, west and north walls.](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/GoA_inst01-496x330.jpg)

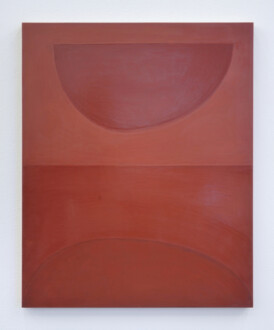

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Carrie Moyer, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/MOY-0116-image-330x330.jpg.webp) Peg Leg and Strawberry Jam, 2012. Acrylic, glitter and graphite on canvas, 72 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery.

Peg Leg and Strawberry Jam, 2012. Acrylic, glitter and graphite on canvas, 72 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery.

"I first heard of Louise Fishman when I was a student at Pratt in the mid ‘80s. At the time I was completely passionate about two things: being a painter and being a lesbian. I was studying mostly with male artists, including a few who would make inane comments like “Of course there are holes (circles) in your pictures, you’re a woman.” A tantalizing rumor about a lesbian painting teacher — Louise Fishman — floated around the undergraduate studios but our paths never crossed. It wasn’t until many years later that we actually met, probably at an opening of Dona Nelson’s. By then I was actively connecting with lesbian painters who had paved the way for me, such as Harmony Hammond and Louise. I ended up writing about Louise on three different occasions and was fortunate to hear lots of stories about her life and evolution as a painter. There are so many things I admire about Louise and her painting: from her lifelong romance with being an artist, to her continuous engagement with gestural painting, to her stubborn insistence on following her own path."">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Suzan Frecon, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/IMG_7176-440x330.jpeg.webp) casta diva (for Louise), 2021. Oil on linen, 24 x 29 5/8 in. Studio view, courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.

casta diva (for Louise), 2021. Oil on linen, 24 x 29 5/8 in. Studio view, courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.

"Louise and I knew each other more distantly early on, but in the 2000s we started to become better and closer friends (I was blown away by the physical reality of her work in the context of the Whitney Biennial during that time).

During a visit to Louise’s studio a few years ago, I was absorbed by some current paintings, lit only by the ambient northern light coming through the studio windows. This light, raked obliquely across the surfaces of the paintings, emphasizing the relief of their physical makeup and the moving expertise of the paint’s application. As we talked, she was seated in front of a painting, perhaps even still in progress. The northern window light came from behind and beyond her, illuminating the painting’s surface from a back and side angle, and casting her face in darkness. It shone over the areas of the paint material and composition. Soon, though I was still listening to her voice, my consciousness was taken over by this highly dramatic play of the ambiguity of the light and dark, and material reliefs.

Dense heavy impastos were interwoven with faint and delicate touches. One can perhaps think of musical dimensions (she had a vast knowledge of music) while trying to describe her paintings, from very loud, smashing crescendos, to the whisper finesse of a dribble or caress of paint, applied directly from her mind-passion-hand, with varied and unorthodox painting tools such as trowels, various painting knives, and many common implements found in hardware stores, even paint-smeared brooms. Her small collection of unique paintbrushes, while not always useable, were cherished, and kept close to where she painted.

Her attachment to certain objects which seem to store energy within them – masterly striking African carved wood sculptures (she studied and drew from similar sculptures for hours in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Ethnology); Chinese Scholars’ Rocks –extended to American milking stools and diminutive objects. As she said; “things in miniature”. Her close attention to things that are beautifully made seemed to inform something about how she handled and shaped material into art – or saw the possibilities of doing so, even in very humble and small objects.

One senses in her painting that she sought out her compositions through the longer work of inventing them herself. There were no shortcuts. Her overall compositions, and the spatial depths in them, her colors, nuances, virtuoso variables of paint material, and lights and darks – all orchestrated within the tableau – take the viewer into multiple dimensions. All of these elements could seem chaotic at first glance. But the longer one looks, the more they achieve their own spatial equilibrium, compelling the viewer to remain looking and looking some more."">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Suzan Frecon, <I data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/SUF02-274x330.jpg.webp) haematites, undated. Oil on wood panel, 29 5/8 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.">

haematites, undated. Oil on wood panel, 29 5/8 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Installation view, floor and west wall.](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/GoA_inst02-496x330.jpg)

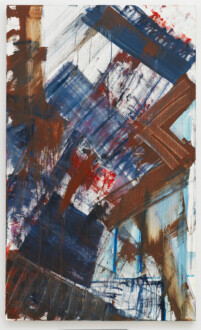

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Dona Nelson, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/DNE02-291x330.jpg.webp) And the Sun Went Down, 2021. Acrylic and acrylic mediums on canvas (double sided), 83 x 78 in.

And the Sun Went Down, 2021. Acrylic and acrylic mediums on canvas (double sided), 83 x 78 in.

“Louise was my friend for over fifty years, and she is still my friend, because her presence in my life will affect me until I die. In 2013, we went to MOMA with a microphone and had a conversation about painting which was transcribed and printed in the 2014 Whitney Biennial Catalogue, which featured conversations between artists who were in the show. It was actually that conversation, in a crowded public place, that, for me, articulated Louise’s intellectual breadth and uniqueness among contemporary painters. As we walked through the museum, we would each stop at paintings we liked and start to talk. Louise strongly liked Jo Baer (Primary Light Group: Red, Green, Blue (1964-65). Louise was a very open and receptive person, genuinely curious and interested in all kinds of art, (young artists loved to talk to her and hear her talk); however, on that day at MOMA, she was unusually firm and sure about the Jo Baer. She looked at the painting very carefully, remarking on how forceful, even and understated the work was. I thought about the Jo Baer while standing in front of a Fishman at Susanne Vielmetter in Los Angeles in September of 2019, viewing a big new painting flooded with bright California light, strokes of stiff black paint, (likely a mixed color), on a blistering white primed coarse linen ground. I thought, ‘What the hell! Why is this so good?’ There is no painter in this country who could pull off that painting but Louise, with her immensely powerful arm in combination with her incredibly sensitive touch. That painting, made by Louise in her 80s, distilled everything that she knew about painting, and was almost like a definition of the complex event that a painting can be at its most elemental.”

A conversation at MOMA, 2013, on Paul Cézanne’s The Bather:

DN: I know this is one of your favorite paintings.

LF: It is my favorite painting . . . What’s interesting in this painting is the way things disappear, the way the area around his legs becomes sky, and the way the thing is sculpted. Cézanne really is a sculptor with paint . . .

DN: It looks like he kept repositioning the figure.

LF: I think I identify with this figure.

DN: What—the carefulness and the solemnity?

LF: And also the physicality of the body. There is such density in the description of the legs and the feet . . . Then, the landscape, it just barely exists, but it’s very tactile. The hills…there’s no definition about what’s back there.

DN: No, and the scale isn’t realistic.

LF: It’s a gigantic figure. A giant.">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Installation view, Louise Fishman, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/GoA_inst04-496x330.jpg.webp) Then & Dona Nelson, And the Sun Went Down">

Then & Dona Nelson, And the Sun Went Down">

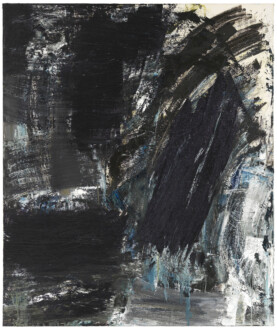

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Louise Fishman, <I data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/LFI01-292x330.jpg.webp) Then, 2002. Oil on linen, 80 x 70 in. Courtesy of the Louise Fishman estate and Ingrid Nyeboe.">

Then, 2002. Oil on linen, 80 x 70 in. Courtesy of the Louise Fishman estate and Ingrid Nyeboe.">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Dona Nelson, <em data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/DNE01-291x330.jpg.webp) And the Sun Went Down, 2021. Acrylic and acrylic mediums on canvas (double sided), 83 x 78 in.

">

And the Sun Went Down, 2021. Acrylic and acrylic mediums on canvas (double sided), 83 x 78 in.

">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Harriet Korman, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/HKO01-331x330.jpg.webp) Untitled, 1995. Oil on canvas, 72 x 72 in.

Untitled, 1995. Oil on canvas, 72 x 72 in.

"Louise and I met in the mid 70's, mainly through painting and the women's movement. We weren't always in touch, but I was always aware of her work - she was very prolific and had many exhibitions. We moved in and out of friendship, as a painter moves in and out of modes and experiences in painting. I feel we got closer in the past few years. Her retrospective exhibition at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, New York, really opened my eyes to the breadth, strength, devotion, and scale of her work. Although one can say that a lot of Louise's work is in an 'Abstract Expressionist' style, if you really study it, you can see that it is unique - completely her own. Louise was completely herself in her paintings."">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Installation view, east and south walls.](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/GoA_inst03-496x330.jpg)

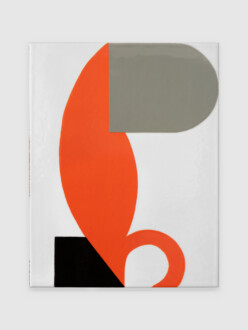

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Ulrike Müller, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/UMueller_xxx1-1-248x330.jpg.webp) Container, 2019. Vitreous enamel on steel, 15 1/2 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Container, 2019. Vitreous enamel on steel, 15 1/2 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist.

“All of the painters you mentioned – Harriet Korman, Dona Nelson, and Louise – have been important to me. There’s so much permission, persistence, rigor, joy, and material thinking in all of them. Also, and here I should add Harmony Hammond to the list, they really helped me see lesbian feminist politics at work in abstract painting – I would say they showed me applied pathways past a simplistic form/content divide and helped me break down the barriers between thinking/feeling/making, in short each of them forged ways into painting and into the studio that were useful to my younger artist self and that I continue to think about today.”">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Ulrike Müller, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/UMueller_wraps-1-248x330.jpg.webp) Wraps, 2018. Vitreous enamel on steel, 15 1/2 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist.">

Wraps, 2018. Vitreous enamel on steel, 15 1/2 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist.">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Louise Fishman, <i data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/FS.28625-copy-1-277x330.jpg.webp) Yes, 2010. Oil on linen, 51 x 42 in. Courtesy of the Louise Fishman estate and Ingrid Nyeboe.">

Yes, 2010. Oil on linen, 51 x 42 in. Courtesy of the Louise Fishman estate and Ingrid Nyeboe.">

![Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman - Louise Fishman, <I data-src=](https://www.thomaserben.com/wp-content/uploads/FS.37920-copy-201x330.jpg.webp) Mon Semblable Mon Frère, 2017. Oil on linen, 50 x 30 in. Courtesy of the Louise Fishman estate and Ingrid Nyeboe.">

Mon Semblable Mon Frère, 2017. Oil on linen, 50 x 30 in. Courtesy of the Louise Fishman estate and Ingrid Nyeboe.">

Selected Works

Louise Fishman, Suzan Frecon, Harriet Korman, Carrie Moyer, Ulrike Müller, and Dona Nelson

curated by Melissa E. Feldman

Opening reception on Tuesday, November 9, 4 -7:30 pm

Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman[br]curated by Melissa E. Feldman Press Release

Thomas Erben Gallery is honored to present Gestures of Affection: In Memory of Louise Fishman, a special exhibition of work by Louise Fishman (1939-2021), who passed away over the summer, alongside that of some of her closest friends and colleagues, Suzan Frecon (b. 1941), Harriet Korman (b. 1947), Carrie Moyer (b. 1960), Ulrike Müller (b. 1971), and Dona Nelson (b. 1947). The exhibition has been organized by independent curator Melissa E. Feldman, who has known Fishman since she began writing about the artist’s work in the ’90s. Thomas Erben knew Fishman through Korman and Nelson, gallery artists, and as a neighbor, with his gallery occupying the same building as Fishman’s studio of over 25 years.

Fishman’s circle consisted mainly of fellow abstract painters. Taking this as a natural point of departure, Gestures of Affection focuses on the genre to which Fishman singularly devoted herself. The New York-based, all-women show evokes the downtown women’s consciousness-raising and feminist art groups that were so formative for Fishman.

Gestures of Affection surveys an artist’s life not only through her work – of which a few major examples are on display – but through these friendships. Nelson and Fishman met in the ’70s through the women’s movement, in which Korman was also involved, as were most ambitious, tuned-in New York women artists at the time. It was during this period that Fishman swore off conventional painting, stitching cut-up canvases into woven grids and making hand-sized object-paintings from found materials.

By the ’80s, Fishman had made peace with the fact that, despite the gender politics around American Abstract Expressionism, she was an abstract painter. However, the rise of postmodernism dismissed any kind of painting besides Neo-Geo and pop-graffiti as irresponsibly apolitical, self-indulgent, bourgeois, and theoretically naïve. Fishman and her contemporaries – those featured here as well as Guy Goodwin, Margery Mellman, Judy Rifka, Amy Sillman, Joan Snyder, and Stanley Whitney, among others – carried on while endgame semiotics and histrionics around the death of painting raged outside the studio door.

The varied practices represented by the selection of artists signals Fishman’s openness to new art and changing times, an openness which might seem unexpected for a lifelong practitioner of gestural abstraction who was drawn to the classics: Chinese calligraphy, Cézanne, Soutine, and Duccio. While there is inevitably some overlap, each artist’s work points to different registers of abstract painting, beginning with the idioms that ground Fishman’s work: the allover composition, the gesture and the grid.

Nelson takes these elements to the extreme in freestanding, two-sided paintings. Stretcher bars themselves become bright grids in these unconventional door- and wall-sized diptychs set back-to-front as opposed to side-by-side. Layers of stained, poured, and hosed-down paint, three-dimensional brushstrokes of paint-soaked cheesecloth, and occasional figurative elements accumulate across every surface.

By contrast, Frecon and Müller’s paintings are studies in simplicity and reduction. While Frecon had been close to Fishman since the ’90s, Müller is a more recent colleague. Both Müller and Frecon craft compositions of clean-edged color, but the resemblance ends there. Müller contributes a pair of characteristically diminutive, jewel-like enamel paintings that reference the world of design, decor and fashion. Given that her practice encompasses murals and woven rugs with pre-pop Warhol-type figuration, the subtext here points to art’s entanglements with consumerism and desire. Frecon’s serene, spacious compositions have no such roots in contemporary life, existing instead in a world unto itself. In the tone-on-tone monochrome haematites (undated) named after the principal form of iron ore and borrowing the mineral’s color, Frecon references nature only insofar as it serves her eye for light, color, and space. The composition of casta diva (for Louise), 2021, is a tenuous arrangement of figure and ground, forest green hovering on an indescribable pink, evoking the same mood as the Bellini aria for which it is named, Fishman’s favorite Maria Callas performance.

Like Müller, her contemporary, Moyer is also a product of the digital era, toggling between surrealism and abstraction in a way that only a digital savant – and former graphic artist – can. She updates these modernist traditions through keyed-up color, smooth, photoshop-like transitions, revivalist mystical imagery, and glitter. The large painting Peg Leg with Strawberry Jam, 2012, dates back to a time when Moyer was engaging deeply with Fishman’s work and writing about it for art publications. The all-over, swirling composition and its unusually raw, unleashed quality reflect the artist’s preoccupation with classic gestural abstraction during this time.

Korman serves as the group’s mediator, her work marking a middle path between gesture and geometry, the intuitive and the preconceived. In the grisaille Untitled, 1996, semi-circles, triangles, and other shapes echo those found in Müller and Frecon’s work, with its expressive brushwork siding with Fishman – at least in this series. Though always cerebral, human touch is fundamental to her work, appearing in the freehandedness of the application and the tendency to overpaint and adjust particular passages. With its practiced unfussiness and penchant for puzzles, Korman’s approach contrasts with Fishman’s more intuitive, unmediated athleticism.

Each of the artists featured here was not only important to Fishman, but to abstract painting more broadly. They, along with Fishman, count among the artists of our time who have kept the genre relevant and vital, each in her own way. Viewed in this group context, Fishman’s work is distinctive in the way that each mark expresses itself physically and indexically: alive in the moment.

Special thanks to Ingrid Nyeboe, Fishman’s widow and manager of the Louise Fishman Estate.

— Melissa E. Feldman, November 2021

About the curator: Melissa E. Feldman is an independent curator and writer whose work focuses on contemporary art in an art historical and cultural context. Recent traveling exhibitions include Indie Folk: New Art and Sounds from the Pacific Northwest, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Pullman, WA (forthcoming, January 2022); Free Play, Independent Curators International, NY (2013-17); Another Minimalism: Art After California Light and Space (2015-16), Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh; and Dance Rehearsal: Karen Kilimnik’s World of Ballet and Theatre (2012-13), Mills College Art Museum, Oakland. Along with her ongoing curatorial projects, Feldman has held positions for the last several years as Distinguished Visiting Faculty at Cornish College of the Arts, Seattle, and Director of the Neddy Artist Awards at Cornish, a private foundation for the arts. Feldman has been a frequent contributor to Art in America and Frieze among other international publications and has also taught at the California College of Art and Goldsmith’s College, London.