Iran via Video Current – a screening curated by Amirali Ghasemi and Sandra Skurvida (Works)

Selected Works

a screening curated by Amirali Ghasemi and Sandra Skurvida

Iran via Video Current – a screening curated by Amirali Ghasemi and Sandra Skurvida Press Release

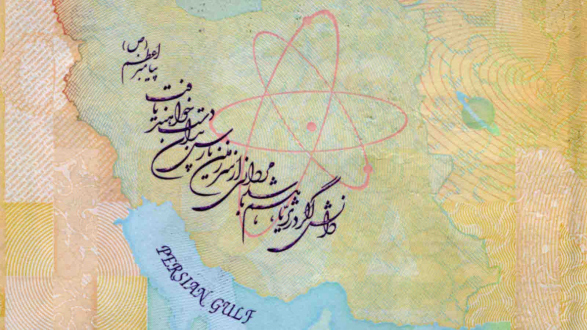

Thomas Erben Gallery presents Iran via Video Current, a project of OtherIS – a curatorial initiative conceived to address cultural production and exchange with countries under international sanctions.

The main question in transnational art production is who represents whom and for whom? This project engages the problem of representation via an ongoing exchange among participants in Iran and elsewhere, as conveyed in the two distinct, yet co-related video programs focused on Iran — one by Tehran-based artist and curator Amirali Ghasemi and another by New York-based curator and scholar Sandra Skurvida. Both curators started their research from their respective locales, yet both programs include artists who live in Iran and elsewhere around the world.

In her program entitled 1979/1357-, Skurvida revisits the sightlines of the most prominent, controversial Western observer of the Iranian Revolution, Michel Foucault. Both his advocacy and the ensuing critique of it reverberate in the appraisals of the recent and current events. The year denoted equally as “1979” and “1357” signifies the difference in time borne out of the societal spaces that are not the same. This negotiation unfolds in the works by Abbas Akhavan, Morehshin Allahyari, Amir Bastan, Bahar Behbahani, Kaya Behkalam & Azin Feizabadi, Barbad Golshiri, Arash Fayez, Mirak Jamal, Farhad Kalantary, Sohrab Kashani, Gelare Khoshgozaran, Amitis Motevalli, Nosrat Nosratian, Anahita Razmi, Jinoos Taghizadeh, Negar Tahsili, and Katayoun Vaziri.

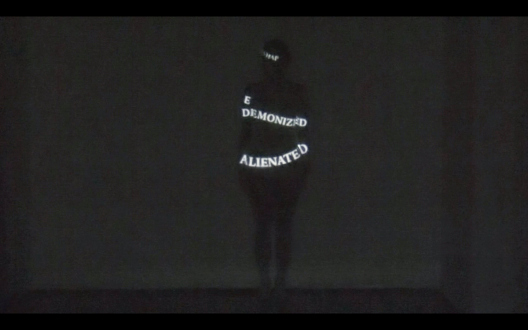

Ghasemi anchors his purview in the present moment and a worldwide network associated with Parkingallery, Tehran, which he founded in 1998. His program, entitled If We Ever Meet Again… (With a Hidden Track), introduces a generation of artists raised after 1979. This generation may be characterized by its responsive attitude — as if it “had no plans,” according to Allahyar Najafi’s video — yet it holds forth a conscious presence in the environment of impositions, sanctions, apprehensions, and expectations. Such a presence asserts an unconditional attachment to the specificity of the origin — apart from the conventions established by the diaspora — yet it extends this original stance towards other contexts, as communication in the personal mode is shared in the featured works by Naghmeh Abbasi, Mehraneh Atashi, Setareh Jabbari, Anahita Hekmat, Payam Mofidi, Shay Mazloom, Amirali Mohebinejad, Allahyar Najafi, Nassrin Nasser, Shadi Noyani, Ramin Rahimi, Shirin Sabahi, Sona Safaie, Bahar Samadi, Hamed Sahihi, and Zeinab Shahidi.